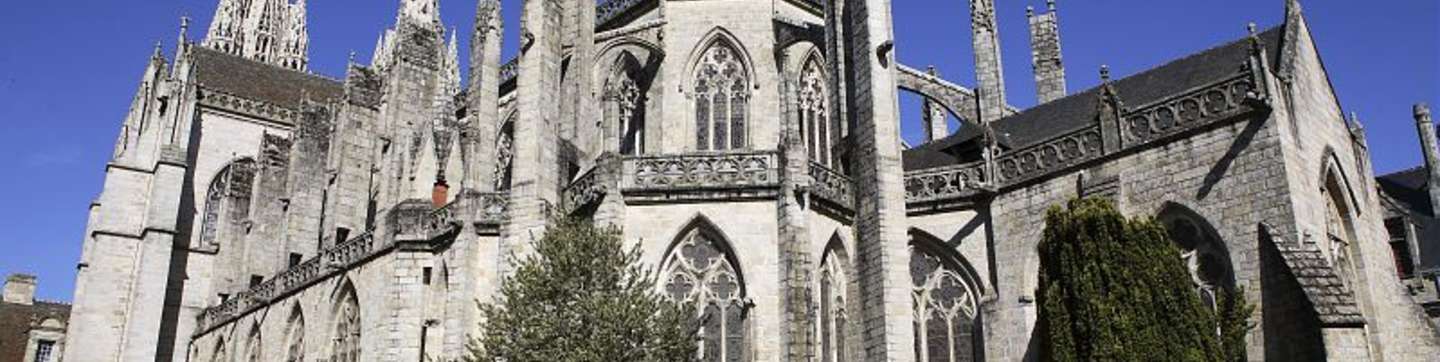

Saint-Corentin cathedral

By the start of the 13th century Philippe-Auguste’s policies – supported by a French-origin administration – had established almost definitively the influence of the Ile de France on Brittany.

From 1239, Raynaud, the Bishop of Quimper, also of French origin, decided on the building of a new chancel destined to replace that of the Romanesque era. He therefore started, in the far west, the construction of a great Gothic cathedral which would inspire cathedral reconstructions in the Ile de France and would in turn become a place of experimentation from where would later appear ideas adopted by the whole of lower Brittany.

The choir presents four right-hand bays with ambulatory and side chapels. It is extended towards the east of 3-sided chevet which opens onto a semi-circle composed of five chapels and an apsidal chapel of two bays and a flat chevet consecrated to Our Lady.

The nave is made up of six bays with one at the level of the facade towers and flanked by double aisles – one wide and one narrow (split into side chapels) – in an extension of the choir arrangements. A prominent transept links the two parts, whose significance recalls the large cathedrals of Ile de France at the start of the 13th century.

The chancel

The date of 1239 marks the Bishop’s decision and does not imply an immediate start to construction. Observation of the pillar profiles, their bases, the canopies, the fitting of the ribbed vaults of the ambulatory or the alignment of the bays leads us to believe, however, that the construction was spread out over time.

The four circular pillars mark the start of the building site, but the four following adopt a lozenge-shaped layout which could indicate a change of project manager. The clumsiness of the vaulted archways of the north ambulatory, the start of the ribbed vaults at the height of the south ambulatory or the choice of the vaults descending in spoke-form from the semi-circle which allows the connection of the axis chapel to the choir – despite the manifest problems of alignment – conveys the hesitancy and diverse influences in the first phase of works which spread out until the start of the 14th century.

The three-level elevation with arches, triforium and galleries seems more uniform and expresses anglo-Norman influence in the thickness of the walls (Norman passageway at the gallery level) or the decorative style (heavy mouldings, decorative frieze under the triforium). This building site would have to have been overseen in one shot. Undoubtedly interrupted by the war of Succession (1341-1364) it draws to a close with the building of the lierne vaults (1410) and the fitting of stained-glass windows. Bishop Bertrand de Rosmadec and Duke Jean V, whose coat of arms would decorate these vaults, finished the chancel before starting on the building of the facade and the nave.

The facade

The first stone of the towers – whose building would last around thirty years – was laid in 1424. It would be marked by ducal will manifested in an extremely active « patronage » which we find in other building sites from the era (Le Folgoat, Locronan).

This facade follows through from the two-tower French facade, nevertheless integrating English influence with the presence of two semi-circular openings under a triangular gable. The towers – themselves originating from Norman bell-towers – follow research of Notre-Dame du Mur in Morlaix and the Kreisker bell-tower at Saint Pol de Léon. The decorative interplay and the proliferation of vertical lines takes our attention from the significance of the buttresses embellished with pinnacles that one finds everywhere in Cornouaille architecture – particularly used as a model – for numerous belltowers (Locronan, Pont-Croix, Saint-Herbot, Saint-Tugen, Carhaix or Ploaré). Elsewhere, even in the smallest rural chapel we find elements of this flamboyant vocabulary right up to the 18th century, the origin of which appears genuinely to be a regional style.

The nave and the transept

At the same time as this facade was built (to which were added the north and south gates) the building of the nave started in the east and would finish by 1460.

Its layout lies in an exact continuation of the choir whilst the aisles align onto the ambulatory and the side chapels. The elevation joins - with a blind triforium- the trefoil balustrade and the Norman passageway to part of the choir. It’s a real archaism of the 15th century. This unity cannot disguise a conflicting aesthetic ; while the choir establishs vertical emphasis with the small columns rising from the base of the pillars at the beginning of the vaults, contrarily, in the nave we see horizontal emphasis, each floor being underlined by a wide band.

The deviation of the nave

The absence of alignment between the choir and the nave raises a number of questions for which there are multiple interpretations. One can generally see, in many other churches but in a less marked fashion, a symbolic orientation copying the position of Christ’s head on the cross. More technical versions are often given – in particular those citing the necessity of placing the nave’s construction on stable foundations by distancing it from the course of the Odet, which a straighter alignment would have made too close. It should be noted that the building of the transept (towards 1460) was put in place last as if pushing aside the connection problems. A particularity of the chapel is the building onto the south side of the choir in order to attach it to the transept. This necessitated the re-opening of the last bay of the ambulatory, which was « extended » thus leaving the pillar without a diagonal rib spring.

For the vaultings of the nave and the transept, we find the same style as in the choir with the continuous lierne. The different coats of arms present on the vault keystones allow more precise dating of the vaults and their painting from 1486-1500. The same dates apply for the fitting of the high windows.

The portals

Isolated from its environment in the 19th century, the cathedral was – on the contrary – originally very linked to its surroundings. Its site and the orientation of the facade determined traffic flow in the town. Its positioning close to the south walls resulted in particuliarities such as the transfer of the side gates on to the north and south facades of the towers : the southern portal of Saint Catherine served the bishop’s gate and the hospital located on the left bank (the current Préfecture) and the north gate was the baptismal porch – a true parish porch with its benches and alcoves for the Apostles’ statues turned towards the town, completed by an ossuary (1514). The west porch finds its natural place between the two towers. The entire aesthetic of these three gates springs from the Flamboyant era : trefoil, curly kale, finials, large gables which cut into the mouldings and balustrades. Pinnacles and recesses embellish the buttresses whilst an entire bestiary appears : monsters, dogs, mysterious figures, gargoyles, and with them a whole imaginary world promoting a religious and political programme. Even though most of the saints statues have disappeared an armorial survives which makes the doors of the cathedral one of the most beautiful heraldic pages imaginable : ducal ermine, the Montfort lion, Duchess Jeanne of France’s coat of arms side by side with the arms of the Cornouaille barons with their helmets and crests. One can imagine the impact of this sculpted decor with the colour and gilding which originally completed it.

At the start of the 16th century the construction of the spires was being prepared when building was interrupted, undoubtedly for financial reasons. Small conical roofs were therefore placed on top of the towers. The following centuries were essentially devoted to putting furnishings in place (funeral monuments, altars, statues, organs, pulpit). Note the fire which destroyed the spire of the transept cross in 1620 as well as the ransacking of the cathedral in 1793 when nearly all the furnishings disappeared in a « bonfire of the saints ».

The 19th century would therefore inherit an almost finished but mutilated building and would devote itself to its renovation according to the tastes and theories of the day.